If you’re not a dog trainer, and even if you are, you can be forgiven for missing the current fuss. I almost rolled my eyes at it and scrolled on by, but then I realised that what happened at the weekend offers useful insights and things we need to take seriously. I hope you’ll forgive me for going off my usual substack Monday script today.

A paper was published by Anamarie Johnson and Clive Wynne last Wednesday in Animals. I’ve refrained in the past from out-and-out criticism of this journal in particular since the whole academic publishing world is icky. There are pay-to-publish journals like Nature which call it an “article publishing charge”, for example. What this means is that journals that were formerly highly respected and selected their articles from submissions now refuse to read said articles unless the authors (or their institutions) pay a substantial charge.

I do appreciate the complexity of sharing academic research, but there are several crises that need addressing.

The first is that there is an overwhelm of research, and it is biased towards studies in which results were noticed. Nobody wants to publish a study in which no effects were found, right? But it’s useful to know that X or Y didn’t work. So, say for example, the study by Johnson and Wynne didn’t find any impact, it wouldn’t be as likely (by far) to get published and therefore we’d never know if and why and when shock collars didn’t work.

The second is that there is a replication crisis. What this means is that a lot of research is not replicated by independent institutions. A second opinion if you will. Sometimes, institutions repeat experiments they’ve already done, but this is not unbiased research on the whole. However, many research institutions want to lead, not to copy. I’m reminded of that line in The Big Bang Theory where Leonard tells his super-critical mother that he had a paper published confirming some research by the Italians, and his mother responds, “So, no original research?”

Institutions (and publications) are very much like Beverley Hofstadter… favouring original research, not replication.

But this is terribly problematic, since a lot of replication studies fail to reproduce results, or find contradictory results. There is a primacy effect at work as well meaning that once a report is published with original findings, it shocks the world or fascinates the world, and then, when subsequent research is published, nobody hears it. That research sometimes completely undermines the original. Sometimes it proves it to be false. Sometimes it confirms it. Mostly, it adds nuance. And then people wander around with a mistaken understanding of science. If you asked me how to correct for this, I’d insist that no new research is published without independent corroboration from a replication study. You think this is unimportant until you realise how much damage the ‘vaccines cause autism’ paper did, or the ‘refridgerator mothers cause autism’ reports. I’m using an extreme example for effect, of course, but pushing back against public understanding of primacy effects in research is hard.

Besides the overwhelm of original research reporting effects (rather than non-effects) and a failure to replicate, there’s also a late-stage capitalism effect going on. It reminds me a bit of Phillip Reeve’s Mortal Engines where cities learn to move and go around eating up other cities. In the research world, this is sometimes called predatory publishing, and MDPI journals, of which Animals is a part, has been accused of this. Charging fees for publication is a part of this. You can read this University of Cambridge article about predatory publication if you want to know more.

However, a lack of proper peer review is also a part of predatory publishing, and this is very evident in Animals. There is a short time period for initial review (which used to take years, by the way, and was very robust if insanely slow) and then time for corrections and then re-review, and then publication. There is a shortage of reviewers, because they’re paid very little in general if at all, but they need to be of the highest calibre, and of course, those people aren’t prone to be paid peanuts to review a paper.

So that Animals charges a fee is not an issue. So does the Journal of Veterinary Behavior, an Elsevier publication. It’s the turnaround of papers. The JVB has a 171-day turnaround, meaning it takes almost six months from submission to publication with rigorous scrutiny. The Johnson/Wynne paper that’s been so controversial this weekend was turned around in 25 days. Clive Wynne, on his FB page, said that he had not expected it to be published so soon. As he said, “This paper came out rather quicker than I was anticipating” (13 September 2024, Facebook page).

Quite.

So there’s been a notorious lack of scrutiny on MDPI journals dating back the last few years or so. I’ve noted Animals papers with interest but little more than that because many editors and peer reviewers have been public on sites such as Twitter in stating their concerns, and when you read the papers, you see the impact of that lack of robust scrutiny.

Worse, Animals is also suffering because of a lack of quality reviewers. The JVB’s editorial board is awash with big names in veterinary behaviour, albeit with a very North American bias. But generally, if some paper gets through that army of highly experienced individuals, then you can trust the results.

So I’ve not been massively vocal about my thoughts about Animals because it seemed a bit childish given the state of the academic publishing industry in general and the fact that many charge fees, there’s a shortage of high quality reviewers even so, the reviewers are often paid poorly and don’t rank highly in terms of their academic background. It’s a fool’s job, in all honesty. However, there comes a time to say, as a friend noted on Saturday, that it’s basically little more than a blog post, albeit with references.

Some of the papers in Animals in the last two years have been absolutely shocking. One, for instance, that referenced a pop psychology book that has been discredited on trauma in humans, rather than actual papers or primary research about trauma in dogs. I mean I don’t let my DoGenius students get away with that, let alone a post-doctoral researcher who is way out of their field.

So it was with much eye-rolling that I even read the paper at all, given the poor esteem in which I hold Animals.

The premise of the paper is simple. A small group of dogs were trained by two shock collar trainers around a lure. There are many, many technical problems with the experiment itself, not least the bias of the trainers. One of the trainers is Ivan Balabanov, a man with a popular YouTube channel who uses shock in his training. I’m refraining from bitchiness and trying to keep to civilities. The other trainer is not identified but also uses shock. Both come with their own biases. They excluded two dogs who were trained with shock because they were non-responsive, and then claimed in the edit when questioned by the reviewer, that the dogs were not statistically significant. I beg to differ. In a small population size, two individuals make a huge statistical significance.

There are both technical issues and reporting issues that I will leave to others to dissect.

What most concerned me and woke me up at 4am on Sunday morning still thinking about, was the section on so-called “ethical considerations.”

I’ll explain why. Wynne, on his FB page on 13 September, made the following statement:

“We are working on a major review of the ethics of dog training and I’ll be in a better position to talk about this when that is done.”

My first question is “who’s this WE?” as in the “we” working on a major review of the ethics of dog training. Upon whose authority? Wynne is involved in Comparative Psychology, not ethics. Does this “we” involve an animal ethicist? Anyone from a welfare background? Or is it just a bunch of people out of their lane and beyond their capacity? Is it ethics by fiat these days?

It concerns me because, from what it sounds like in this statement, the ‘study’ (it’s such nonsense on every level that I churlishly refuse to qualify it as research) will be used to support this ‘review of the ethics of dog training’ even though Wynne - in my opinion - has no right to be on that panel of whoever ‘we’ might be. He is not a behaviour science professor as far as I am aware, and so is in no good place to critique the science or technology of training that is largely based on operant methods. In fact, dog training goes way beyond operant methods, and so it would logically need to involve someone with an exceptional knowledge of respondent behaviour as well, and instinct. What will this “major ethical review” contain? It sounds like shock will be part of their mandate which is massively concerning.

Over the past five or ten years, it’s become evident that Wynne takes a lightly contradictarian position. He seems to like to refute whatever comes out of Eötvös Loránd University for example, and anything that supposes a more cognitive basis or social basis for animal behaviour. I’ve usually read his comments with some interest because I think it’s important not to get carried away by complex cognitive explanations when simpler Pavlovian or Skinnerian processes are evident. And it’s important to have such voices. I agree with him on many points, such as the significance of a dog’s understanding of human words. But dogs are more than Cartesian machines, no matter what his study suggests.

And he favours a focus on dominance and favours the (very weak) science on this, and at times, his position has seemed ludicrous. For example, he is not a fan of explanations that dogs have evolved or been selected to follow human gestures, such as the work of Michael Tomasello and Brian Hare, and yet here he is, using trainers who breed dogs (Balabanov breeds the Ot Vitosha line of sports malinois) who are selected because of their ability to follow human cues and gestures for competition purposes in ways that go far beyond the average streetie or mutt on the street.

I do thank Wynne for his own clarity about his thoughts and although I do not always agree with his take on things, the fact that he is an open book on the whole is refreshing.

For example:

So it’s a little concerning to hear this “we” that goes without clarification as to who might be involved in this “major review of the ethics of dog training”. The language of it is also concerning. Major?

And at whose behest?

Involving whom?

How does one go about being selected to be on the board of such a review?

France, for example, had a major review of companion animal welfare. It involved three major agencies: animal welfare scientists & charities, the French kennel club and the French national veterinary university. The aim was a political cross-party agreement and consensus. The findings led to a change in law, led to minimum standards for all people who work with dogs, including hobby breeders, welfare agents and even people in garden centres that sell animals. It led to an agreed curriculum that is delivered by agreed agencies to anyone whose lives regularly involve handling companion animals (including rabbits, ferrets, birds, reptiles and rodents).

But no grand claims were made about it and they certainly did not take this weird “ethical” standpoint to justify the use of shock collars that is being taken by Balabanov and others. In fact, all three agencies were agreed that shock, prong and choke should be outlawed.

I’ve posted about this before on Facebook a number of times. The first was back in 2017 when I first heard claims that a failure to shock or otherwise punish dogs was putting dogs in the shelter. It isn’t, and I have strong evidence to support my take. It’s not just an old lady clutching her pearls and shouting at clouds. Dogs who have been ‘trained’ with a shock collar or other forms of punishment are exponentially more likely to end up being euthanised in my experience, and to suffer with all kinds of fallout. A dog who has been trained to sit for a biscuit is an easy dog to rehome. If we got those kind of dogs in the shelter! I find this attempt to justify abusing animals utterly abhorrent.

It reminded me very much of a line in Judith Butler’s book Who’s Afraid Of Gender? in which she uses a term ‘moral sadism’. Ironically, it can very well be summarised by Wynne’s sarcastic jibe about the Monks of New Skete releasing a book about gently teaching your children manners by using a big stick.

You’ll know moral sadism by its worldly form: it’s for your own good. We have to be cruel to be kind. It’s a necessary evil. I wouldn’t punish you if you didn’t need it. This is saving your life. Spare the rod and spoil the child.

I see that moral sadism absolutely enmeshed in arguments that a failure to hurt, abuse or otherwise punish dogs puts them in the shelter.

In her book, Butler talks about how moral sadists create a ‘phantasm’ out of their fear. They make up tales and stories and anecdotes - or even rely on the occasional real-life evidence - to frighten their believers into believing cruelty is necessary. She’s talking about gender-phobia, transphobia, anti-homosexuality and anti LGBTQIA+ policies and beliefs, but she might as well be talking about all kinds of fears whipped up by hatemongers who capitalise on just how easy it is to do this to a population.

I couldn’t help but hear it in Donald Trump’s dog whistle last week that was so outrageously phantasmagorical that it actually made people laugh rather than making them scared: they’re eating the dawgs… they’re eating the cats… In Springfield Ohio, they’re eating the dawgs…

To quote the moderators, no reports of migrant populations eating companion animals have been received by the Springfield municipal authorities.

The trouble is that so many of these imaginary scenarios are not quite as easy to see and ridicule. And yes, people eat companion animals. Yes, it has been a racist trope since forever… the Chinese communities accused of serving up cat and rat, the Indian, Bangladeshi, Bengali and Pakistani communities accused of eating pets… And yes, good old Hitler and his Nazi propaganda used it in theirs. But it was so specific and so outrageous and such nonsense out of Trump’s mouth that most of us found it ridiculous.

We’re not there yet with the lies about shock collars and punishment. We’ve not reached the point where these imaginary scenarios they create in their head are so ludicrous and silly that they make us snort with the ridiculousness of it.

And most people have no idea why dogs end up in the shelter. It’s a plausible belief that using rewards or not training dogs at all cause dogs to end up there.

I want to dissect the “ethical considerations” section of the paper properly so you’ll see what I mean.

I’m taking this directly from their paper:

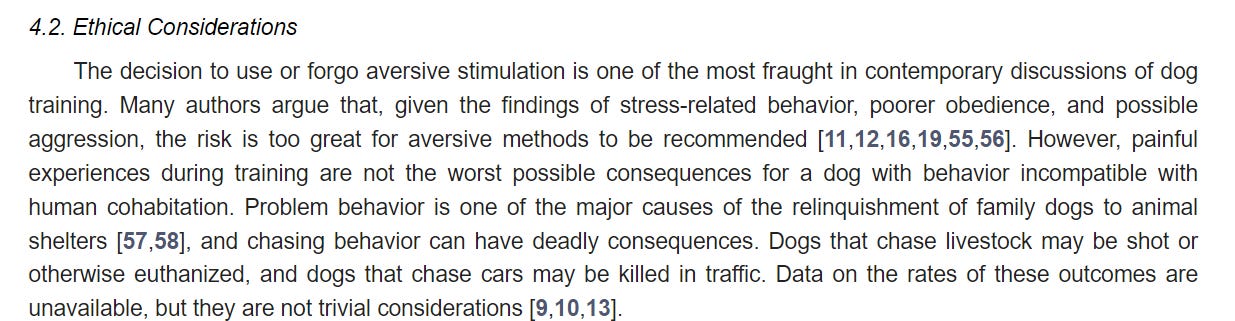

So the paper suggests that “problem behaviour is one of the major causes of the relinquishment of family dogs to animal shelters” and that “chasing behaviour can have deadly consequences”. They are not “trivial considerations” according to the authors, although they admit they do not have data on this.

We know these things exist: people do surrender dogs. Dogs die chasing stuff. As they say, “dogs that chase livestock may be shot or otherwise euthanised” and “dogs that chase cares may be killed in traffic.”

These are plausible. Fantasies, as I’ll explain, but plausible fantasies. Or of such trivial consideration that they don’t bear study when research and funding is not infinite and a strong welfare argument could be made that we should and could rightly look at the changes to a dog’s life that would make the biggest impact. Wrap a lie up in a truth, though, and it’s easy to make it plausible.

Ergo, they suggest by inference, shock collars are necessary. The very definition, by the way, of moral sadism - using “ethics” to suggest that pain, punishment and cruelty are justifiable on moral grounds.

But let’s deconstruct this.

Do people surrender dogs because of behaviour problems?

I mean of course they do. But, as someone who has done those surrender interviews over a decade, there are many reasons bigger than that.

Moving into rented accommodation is a big reason. This week, the UK Labour government were promoting their proposed Renters’ Rights Bill. Dogs Trust support this bill because, according to them, around 15% of relinquishment requests are because landlords refuse to accept pets. As this article says, quoting a representative of Dogs Trust, “One of the most common reasons we see dogs handed in to our rehoming centres is due to a change in the owner’s living circumstances and a lack of available pet-friendly accommodation, forcing them to make the heartbreaking decision to rehome their pets.”

I’d add divorce, separation, change in jobs, change in health, entry into sheltered accommodation, housing insecurity or financial insecurity into the mix.

So where IS problem behaviour that can be solved by a shock collar on the list of relinquishment priorities?

And one single solution - lobbying governments to change rental laws - would make a huge difference to surrender laws.

But surrenders are not the only reason dogs end up in a shelter. For our shelter, around 15% of dogs were surrendered legally. You know, where a person calls the shelter and says they need us to take their animal.

Plus, people lie to avoid shame and stigma. Even if you think you know why people surrender their animals, you don’t. In other words, problems in managing their dog could be over-reported or under-reported. It’s a hell of a lot easier to say ‘the dog is an arse’ than it is to admit you can’t hold down a job because of a dependency issue or lack of financial stability or because you’ve been unhoused.

One of the studies that Johnson and Wynne quote is from 25 years ago. In America.

That’s often the problem with a lot of research: it supposes whatever is happening in America is not only true of the rest of the world, but applicable to the rest of the world.

So, in the shelter where I was a trustee, we had roughly 500 dogs on the shelter side. If we take the 15% surrender rate to be roughly true, that’s 75 dogs. If we rank problems for France (where landlords do not automatically have the right to refuse housing to pets) then divorce, change in financial situation, change in work hours, ageing, physical health and mental health far outstrip ‘this dog was untrainable’ as reasons people gave for surrender. It’s not to say it doesn’t happen. It’s to say that it was probably true for about 5 out of those 75 dogs. Or about 1% of dogs in the shelter.

Now you could argue that 5 dogs is 5 too many. 1% could be reduced to 0.5% through shock collar use, maybe. But that argument is a tenuous one not least because when I first started volunteering at the shelter in 2013, you’d have been hard pressed to find a trainer in the area who wasn’t using aversive methods. There was one, I think, but he was the exception. Most were using (non-shock) methods to train dogs that varied from Cesar Millan style ‘ssshht’ and standing and helicoptering and 23h crating to whipping dogs with lunge whips and chains. I trained Heston, who arrived with me in 2012, ironically through watching Zak George videos on YouTube. I may not think he is the best trainer in the world, but it was better than the alternative even though I didn’t know why. Plus, I couldn’t afford training and it was very far away and inconvenient. Still, I did my best and Heston came out okay, despite my inadequacies, and perhaps those of Zak George, who knows? So there are other factors like accessibility to training, financial aspects to training, geographical accessibility and other stuff that are also impediments to why people don’t train their dogs. It’s not all, as Balabanov, Johnson and Wynne insinuate, that people are lazy and simply concerned about speed and results. I think that’s a very cynical and biased stereotype that is not rooted in evidence. It’s, as I always say, more complex than that.

But there may be, in those other 70 surrendered dogs, those whose owners lie about the reason they’re surrendering animals, and lack of training could well be one. Just as there could be, in this estimation of 5 in 75 surrendered dogs whose guardians say their dog is poorly trained or not trained at all, when in fact this is not true.

It’s impossible to really say. The people who could say are those involved in surrender, but we’re all loaded with biases. A lot are about impaired relationships. I’m going to give one as an anecdote. This is a true story and I have not changed any of the details as I usually would.

Ben.

I received a call about Ben back in 2017. He’d attacked a child in the family. He was a hound who’d come from a local rehoming association as a puppy and he was 18 months old. There had been some low level growling for which the family had sought advice from a popular local trainer. The trainer recommended and carried out a ‘board and train’ which involved, according to her own family, 23h 30m of crating in a small travel crate, and 30 minutes of daily “training” with collar jerks, “shhhhtting” the dog and physical violence towards the dog if he exhibited any aggression. For reasons I won’t go into (extinction, contextual renewal and the pointlessness of punishment) Ben came home, had 5 very subdued days, then attacked (no biting) a child in the family worse than he ever had.

I spent 7 fraught hours with the family who were very tearful. The teenage boy was clearly experiencing mental health issues and was beyond coping. I left a plan to help them rebuild their relationship, but when I got a call the next morning, I simply phoned the director of our shelter, asked if they could surrender Ben even though he was out of our catchment area, and she said yes. He was rehomed in Germany within three weeks as I’d arranged it with the German team - full disclosure over what had happened - and I’ve followed his progress over the last seven years which has been without incident.

Rehoming a dog who is struggling in one environment is not the worst thing that can happen. For Ben and his human family, it was the best. They got another dog and didn’t use force, and Ben got to restart his life with people who hadn’t used force which had destroyed their relationship.

And for my girl Tilly, same. With the tragedy that it truly is, the relationship had become so impaired that she was threatened with euthanasia. In my home, it took a while and a bunch of kindness, but there were no behaviour problems.

I should also say that Tilly’s behaviour was, in my opinion, not only worsened by punishment but also created by it. Her being punished for guarding her toys when the children tried to take them from her led directly to her consultations for sudden onset of “submissive urination” and a lack of housetraining. In other words, being punished made her wet herself. Living with me, my partner at the time, his son and our companion cats, dogs and chickens, and she not only lost her guarding behaviours towards humans but also stopped wetting herself when people stood up or approached her. And, although she came as a chicken chaser, she was easily trained without punishment, harm or coercion.

This, for me, is the bigger question.

How many dogs are surrendered because punishment - including shock collars - has damaged the relationship with the family irrevocably?

Because it’s - in my experience - a much, much bigger number.

Those dogs are also incredibly difficult to place.

But of the 425 other dogs in any given year in the shelter, of course there were untrained dogs, those trained with sandwiches (as Tilly and the chicken here) and those trained with aversives, on whom we had little history. That doesn’t mean they don’t have data or stories that are known to pound staff.

Lots of ‘found’ dogs who come in via the pound are a) known and b) surrenders by the back door.

Ralf was one of those.

In 2014, he was picked up 4 times by the pound. He was the guard dog for a sawing company south of the city. Born in 2001, he’d had a 13 year clean record. In 2014, however, he kept being ‘found’. Sick of paying the €100 fee each time, plus kennel fees and the likes, the company simply failed to pick him up the fourth time. Would a shock collar have stopped him straying?

A better question is whether the company who owned him wanted to stop him straying, or if he was, as we suspect, a surrender via the back door because he was old and they’d already replaced him with two malinois who were more fierce.

In other words, using ‘shock saves dogs from the shelter’ fantasies as reasons to justify their use as ‘ethical’ (!) is not based on evidence, not based on reality and fails to take into account the complex reasons that animals are surrendered or end up in the shelter. It also fails to take into account those animals whose relationships are irrevocably damaged by punishment and who are then a liability to place.

I’ve noticed more people calling out this nonsense justification and thank God for that. Keep calling it out. It’s untrue that punishment would save dogs from relinquishment.

You know what WOULD massively and substantially lower the number of dogs in shelters, by the way? Reducing hunting with dogs, using ‘security’ dogs to protect property and abolishing greyhound racing. Hashtag Just Sayin’. Nobody wants to talk about that. Lobbying at its best.

So I’ve long since seen that ‘shock saves animals from the shelter’ for the morally sadistic excuse (and lie) that it is. In the same vein as banning immigration would stop dogs being eaten in Springfield, Ohio is a nonsense excuse too.

But the report has another one - it would reduce dogs being killed on the road.

I’d like to point out here the final sentence of their paragraph: “Data on the rates of these outcomes are unavailable, but they are not trivial considerations”

Well, data IS available. It’s not brilliant data, but it’s data. And what it suggests is that it very much is a trivial consideration. Not that anyone whose dog has died on the road thinks it is a trivial consideration. But it’s not a viable statistical consideration to justify shock collar training, or even promote it as more efficient.

Where is data available on road deaths? From municipal authorities or pounds who retrieve dead animals on the road. Yes, I have that data for our small area of 350,000 people. It actually also includes data on injuries probably caused by the road. This data is part of all data collected by pounds in France, for example. I can’t speak to other countries, but there IS data. People could get that data if they want.

For example, when a companion animal (dog, cat, ferret, rabbit, pot bellied pig - etc) is picked up by a pound in France, they are logged. That log is shared with the state vet department. The state vet department pass it to the National School for Vets who are charged with collating that data. They, in turn, feed it to the government. It’s France. There’s paperwork. Thank Napoleon. The government use this to work out that for every 1000 inhabitants, there are 3.87 stray animals per year. This includes dogs, but is not exclusive to dogs. They then tell councils (who are responsible for managing stray companion animals) who are then given financial figures to allocate to the management of stray animals in the 8-10 days they are legally obliged to keep the animal housed and alive. Thus, a department (like a county) can work out if they have half a million residents, how many stray animals they will be expected to house throughout the year, and how much it will cost, how much to budget to the services that provide that care, including picking up the animal, housing the animal and doing the euthanasia at the end of the 8-10 days if that is their policy, as it is for about a third of French pounds.

The animal is also checked by a vet. Ostensibly this is for disease management, but also to protect against litigation. Nobody can claim that their dog was injured in the pound if the dog was found injured and this injury was witnessed by a vet. The dog or cat or ferret is microchipped if they are not already (it’s the law) and this charge will be passed on to guardians if they are reclaimed, or assumed under the pound’s running fees if not. This is true even if the animal is euthanised 8 days later. No vet can euthanise some random animal. So we know how many injured dogs come in because their treatment fees are paid by the pound in the first instance until the guardian is located. So we know how many dogs (and cats) have injuries consistent with a road injury too. Available data.

But… this data is not complete, and neither can it be. Not all stray animals are picked up. Many animals return home of their own volition or are reunited via other means. For the dogs I’ve personally found in the last ten years, only two made it as far as the pound. The rest were picked up because their number was on a collar or their owners had placed an appeal on social media.

Some stray animals who are killed or injured by cars do not come into the pound if they are reunited with their family or their bodies are not found. Cats vastly outstrip dogs as you might imagine.

So it’s hard to get good estimates, but it’s not impossible. The only problem is that these numbers are so small as to be statistically insignificant. For example, on average, the pound would pick up around 5-10 dead dogs every year for a population of 350,000 people, out of around 1600 animals who come in to the pound. There are also social media sites that record dead animals, like Pet Alert does. They have a folder entitled ‘have joined the stars’ (a rejoint les étoiles) in which animals who have died are recorded. Not all of these come in via the pound, and not all animals killed or injured on the road are recorded. Some dogs are never found having gone missing.

But even so, these numbers are very, very small. Enough that you remember the dog. Of the 5-10 dogs who are found dead or are euthanised in the pound, some are very old and one or two are euthanised because of their health, not because they were hit by a car. One or two are killed by cows or horses or cars.

But of these dogs, are they, as the study says, killed in traffic because they were chasing cars? The numbers would be so ridiculously tiny. Of course, it may be one or two over a ten-year period in a place of 350,000 people.

Is this enough to justify shock? These individual cases?

There are so many problems wrapped up in this ridiculous fantastical creation of fictitious reasons to shock dogs for so-called ethical reasons that it doesn’t bear studying in any seriousness. But because it’s a plausible fiction that it might matter, then people believe it and justify using them. Likewise, by the way, dogs who attack sheep. Again, in a ten-year period working to retrieve dogs reported to the police or state vet (the pound managed the retrieval, alive or dead) livestock killing was so rare that I can tell you every incident in which a farmer reported it. And they do report it, (they over-report it in fact) because they get financial recompense for livestock killed by wild animals or dogs. But they have to have a report from the state vet otherwise it’s not honoured because otherwise the farmers would be claiming all kinds of compensation. I have studies for these numbers, by the way.

So data is available. They wouldn’t like it if they looked at it because it in no way suggests that shock collars are the answer to this entire fiction they’ve created.

Anyway, I did a live about it on Saturday night. I didn’t want to get into the technical and academic reasons this paper is nonsense, but I did want to air this. It was so important that I suspended my usual Monday substack-ness to do it. Sorry, not sorry. In the end, because of that “ethical considerations” paragraph, and because of Clive Wynne’s intimation about some unknown body doing some “major review of the ethics of dog training”, I thought it more than something I should roll my eyes about and scroll past. I can see there are movements afoot to use these fictions and occasional anecdotes as justification for the use of shock collars and I find it utterly abhorrent that such logical fallacies are used in what is presented as ‘research’.

I have no way of knowing whether the authors or the trainers involved genuinely believe it is the case that shock collars can save dogs’ lives or if they’re using these fallacious arguments to justify sadism knowing that people won’t tackle them because they sound plausible. Anyway, I thought it worth tackling. Important to tackle. I feel like this paper needed an NBC moderator to step in and say, “Actually, Clive, Anamarie, Ivan, we’ve talked to the municipal authorities and they say there is no credible evidence that dogs are being killed or injured chasing cars in numbers significant enough to justify shock.”

Plus, if they are (and I know a number of car chasers who were hit by a car at least once and who would not respond to shock, like the two they excluded from the study) is punishment the answer to that problem? Although they quote Steve Lindsay as justification for using shock in such a case, Lindsay actually says, “The allure of chasing moving objects can be so potent that dogs will often continue to engage in the behavior even after being hit and seriously injured.”

If being hit by a car isn’t enough to stop you chasing them, what amount of shock is?

I’d like to believe the people who trust in shock collars genuinely believe they are on the side for good, but how do we help reset this trick of the mind when (if?) they’re so convinced they’re saving dogs’ lives?

Anyway, enough of my pulse-raising on a Monday morning. Normal services will be resumed next week, assuming there is no ridiculous “research” published to boil my very blood.

Have a great week, lovely people and don’t despair if this latest nonsense seemed to make our goal of a better life for companion animals seem even further away. We are many!

Thanks for posting! I briefly skimmed something about this issue on social media and forgot to return to it. Appreciate your take and added context, because I had no idea who these people are. I've been developing an interest in research, too - are there any journals that you recommend following?