Is cooperative care with dogs pointless for vet visits?

Making our vet visits less challenging for our dogs

My boy Heston was a typical candidate for cooperative care. Aged 1, he panicked on the vet table and wet himself. I spent a year doing cooperative care activities with him, including finding a platform I could raise and lower pneumatically and desensitisation to the vet surgery. We had over a hundred exposures and plenty of cooperative care cues.

Yet on his annual vaccination trip aged 2, not only did he wet himself when he was unceremoniously yoinked onto the table despite my protestations, his anal glands also went too.

I left feeling utterly disheartened; I actually skipped annual vaccinations for two years and thankfully, he didn’t need the vet for anything else. As a customer and caregiver, the whole experience left me avoiding the vet surgery.

Could this study explain why?

When studies don’t say what you want them to say…

An Austrian-Swiss pilot study into whether cooperative care reduced physiological markers of stress was published in the Applied Animal Behaviour Science journal in 2022. Wess et al. (2022) is free (as of October 2023) to download from the Elsevier site here.

It was one of those reports that you don’t really want to read because it doesn’t say what you wished it would say.

What I wished it would say was that cooperative care protocols significantly reduced physiological markers of stress for the control group compared to the test group.

That would have been wonderful, wouldn’t it?

Yes! Cooperative care is important for dogs. These are things we can teach! As someone who couldn’t be a bigger fangirl of Deb Jones, Eileen Anderson and Laura Monaco Torelli, you can understand that cooperative care is close to my heart. I value it. I would like for them all to be world-famous names across every mouth.

Instead, this report seems to suggest by deduction that it’s a waste of time. Instead of spending all that time trying to find cheap platforms that I could rise and lower, I could have been in a bar, having a nice cocktail… well, we could have spent more time on walks and wanderings, at the very least.

Those words, ‘compliance was lower in the TG [test group]’ (that’s to say the group that did some cooperative care stuff) initially sounded like the death knell of my visions that cooperative care would become normalised and everyone would be doing it to reduce stress in veterinary clinic settings.

It gets worse. The results were that: ‘Overall, transfer of trained skills to the veterinary examination performed by a team blinded to the group allocation was poor.’

So it seems like cooperative care is not the answer we’re looking for, jedis.

However, when I re-read it, the report said exactly what I’d expect it to say.

So what would we expect it to say?

We would expect it to report back what it did. In part, at least. Initial fear conditioning is really powerful, and extinction learning is a competing process which is weak. Those initial vet visits can cause so much fearfulness that fighting back against that learning is really tough and easily derailed.

That’s exactly what I found with Heston, too.

Back it up though. Let me just clarify those two terms and find some appropriate citations.

Fear learning is a Pavlovian process. There are certain experiences which are (almost) universally aversive for our species. High temperatures and electric shock are two for humans. I say ‘almost universally’ because they are automatic, involuntary, physiological responses and that depends on the integrity of the reflex arc.

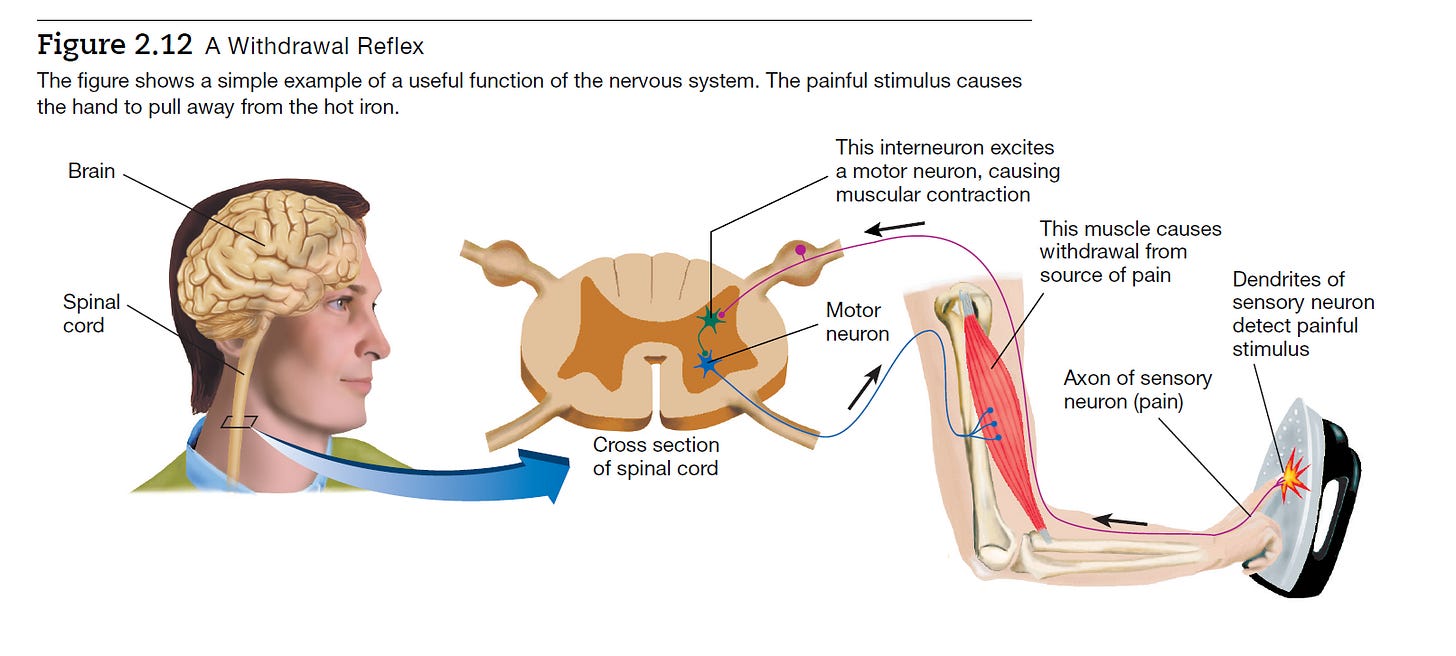

As you know, the reflex arc has afferent (intake) bits. They’re the sensory-perception bits. It also has central processing bits that translate that information and pass it forward. Then there are efferent (output) bits. Those are the motor responses.

This diagram from Carlson & Birkett’s Physiology of Behavior (2018) shows that process nicely. Touch the iron and the afferent dendrites detect it, pass it along to the interneurons in the spinal chord and the interneurons pass it on to the motor neurons to tell your finger to move off the hot stuff.

So why ‘almost universally’? Because sometimes, bits of those processes don’t work. Working out which bit is informative, and vets do this when they do ‘knuckling tests’ on dogs for example. A non-surgical, non-invasive test of whether the reflex arc is doing what it should. Guy Leschziner’s marvellous book The Man Who Tasted Words (2022) gives some curious examples of where human sensorimotor reflexes don’t do as they should. The handful of people in the world whose pain receptors don’t work are testament to the fact that reflexes are an ‘almost universal’ thing and there are many conditions that affect them.

That’s physiological reflexes. The stuff of Pavlov.

What about emotional reflexes? The stuff of John Watson, Mary Cover Jones and hundreds of emotion researchers since then…

Emotion reflexes

Emotion researchers agree on very little. Since the beginning of psychology, psychiatry and even philosophy and natural science, they have disagreed on what emotions are, who has them, how they differ from moods or physiological state and how many are universal. Add in neuroscience, anthropology, sociology and cognitive psychology and you’ve even more disagreement.

That’s particularly marked where biology crosses over into philosophy and linguistics, especially since neuroscientists who study emotions aren’t always grounded in linguistics and language development.

If you ever want to understand how scientists fall out, by the way, Noam Chomsky and BF Skinner had some pretty outstanding polarised arguments about language development. Whether it is reinforced and constructed or whether it is discrete and innate were hot topics in the 1950s and 1960s. If you want to know how bad it got, know that a bunch of behaviourists of the Skinner school called their chimp Noam Chimpsky as a scientific burn. It backfired a bit because they weren’t able to teach Noam Chimpsky to speak… despite their conviction that any primate could acquire language through reinforcement-based associative learning, and Noam Chimpsky certainly did not acquire sign language as well as some other chimpanzees such as Washoe, or gorillas such as Koko.

By the way, my opinion is that they were both right: human language IS innate and it IS learned. And they were both wrong to insist that their field was the only method of language acquisition. Pretty much the same debate is happening now about emotions.

In the ‘emotions are universal and therefore involuntary to some degree’ corner, we have heavyweights such as Darwin, Paul Ekman and Jaak Panksepp. They don’t all agree, by the way, especially since Ekman’s work was in humans and Panksepp’s was in rodents. Panksepp neatly bypassed the whole query by calling them ‘affective pathways’, almost suggesting mammals have the hardware but stopping short of saying it has the same function and software as it does in humans. There are flaws in Ekman’s approach and also in Panksepp’s which leave them open to the ‘emotions are a construct and are socially acquired’ corner, mainly occupied by Lisa Feldman Barrett.

Based off her popular book and TED talk, Feldman Barrett is mostly wrong because her evidence of reinforced learning is deeply linguistic in nature and incredibly, incredibly narrow because a) she’s not a linguist and b) she doesn’t, as far as I know, speak another language which means she was wrong about a lot of the linguistic stuff related to language, like just because the Germans have the word schadenfraude doesn’t mean that English speakers don’t feel schadenfraude too. The notion that we learn ‘this is fear’ from linguistic labels and familial or societal conditioning is very flawed. There’s lots of flaws in her pop fiction, which is a shame because her published papers are more circumspect. I will be picking them up in other posts as they are worth discussing as they relate to dogs, since her views are (in my views, erroneously) influencing dog trainers.

The problems with considering emotions as a construct based on language are manifold. One of the problems is that it excludes anyone who doesn’t have language from having emotions. Deaf and blind people, for instance. And animals. It’s also troublesome for prelinguistic humans and humans who can no longer express themselves in words. Considering emotions as entirely social & cultural cognitive constructs is an extremely flawed way of looking at them, especially when we consider comparative psychology. The problem is that language and emotion are deeply intertwined in human cultures, so it’s more complex than simply cracking open the hood of the brain, so to speak, and having a rummage around inside like we can do for sensorimotor experiences.

As it relates to dogs, I don’t think anyone with a dog would fail to see emotions.

We always face that challenge of anthropomorphism (does the dog feel ‘guilty’?) vs denialism (animals don’t have emotions at all) that haven’t been easily explored because they’re so divisive and it’s easy to take lines that justify notions that emotions are constructed and never reflexive?

Is there any way to reconcile the innate-nature-universalists such as Ekman with the learned-nurture-constructs such as Feldman Barrett?

Kind of.

Even the most hardline emotions-are-a-construct believe there are forms of reflexive emotion. Feldman Barrett herself simply goes down the line of good-bad/pleasant-unpleasant or positive-negative. In other words, stimuli in the world can cause involuntary positive or negative affective states.

Largely, most emotion researchers would agree that there are largely innate, quicker, involuntary physiological responses involving more ancestral subcortical brain structures and there are more constructed, reflective, experiential, learned, voluntary cognitive processes.

There’s lots of ways to talk about these.

If you’re a Kahneman fan, System I and System II.

If you’re a Mischel fan - oh he of the marshmallows - hot and cold.

If you’re a Siegel fan, downstairs and upstairs

So most emotion researchers agree that there are some more ancestral emotions operate on more of a stimulus-response mechanism like a reflex. They also might agree that there are more constructed, culturally nuanced emotions that involve more complex learning. There are different types of emotions, then. And some are more complex than others. Some may be shared with other species, and some probably aren’t - at least in the form that we experience them for sure.

My line is that if you spend 40 years creating fear in rodents and then say fear is a cultural construct that exists only in humans as clearly you’ve not been paying attention to your test subjects. You can’t say ‘emotions don’t exist in animals’ or ‘(some) emotions aren’t physiological in nature’ if your work depends on shocking rodents until they freeze.

Even the most hardline of the emotion researchers like Feldman Barrett who believe that emotions are human linguistic and cognitive constructs believe that rats can experience fear. If it makes you feel more comfortable to imagine I put air quotes around ‘fear’ as if it’s simply something akin to human fear, go for it. If you want to imagine that I put ‘sham’ in front of fear, feel free. If you feel better thinking of ‘fear-like’ when you read fear, I’m happy with that. Neither of us is right, and neither of us is wrong.

Personally, my line is that when it comes to dogs, not only do they have ancestral, largely involuntary responses that emanate from subcortical structures and act as an adaptive motivator of behaviour, but they also have more complex, voluntary, anticipatory learned emotional responses that emanate from more complex cognitive cortical structures and involve more complex learning histories. Expectant and anticipatory affects based on complex learning, like frustration, anxiety, disappointment, surprise, prediction, expectation, anticipation, excitement, hopefulness, discouragement, relief and even trust are not off the table in dogs as far as I’m concerned. Yes, they will be experientially canine in quality, and that may well be experientially different from humans in many respects, with fundamental similarities. That’s my view. It goes way beyond Panksepp and the likes. I have reasons and will expand on those liberally at other times.

Anyone who has picked up the dog’s lead and opened the door to rain cannot fail to appreciate dogs feel disappointment. Just because dogs can’t articulate that experience doesn’t mean they don’t have them.

At this point, I often see Wittgenstein’s quote that ‘if a lion could speak, we could not understand him’ bandied about about in proof that the animal umwelt is so experientially different from ours that even if they could articulate it, we could not understand them.

I like to remind people that Wittgenstein, as a German speaker living in an English-speaking world, was actually using this as a metaphor to explain that the private experience of any other human is so radically different from ours that they might as well be a lion. As an English teacher, I have taught many dyslexic students, but I cannot understand how it feels to be dyslexic even though my students and I talk about this uniquely human experience all the time. Kind of proves Wittgenstein’s point if we can’t understand such a common human condition simply because we don’t have it.

All this to say I think there are reflexive, more automatic fears in dogs and there are more anticipatory, learned fears. Just because they can’t articulate them doesn’t mean they don’t exist.

Fear as a stimulus-response vs fear as a learned response (and anxiety)

I have clearly not thought this through entirely, yet. My take on it is this:

Dogs have those discrete, automatic, involuntary fear responses to stuff. That stuff is pretty similar across the species, just as fears and phobias in humans are pretty similar for us. Strange people. Strange dogs. Loud noises. Constraint. Probably other things.

This fear operates like a sensorimotor reflex startle response. A car backfires, you jump. Just like sensorimotor responses, they’re subject to habituation and sensitisation. These are Pavlov’s unconditioned fears. In other words, we don’t have to learn them. Socialisation can push back against things that are normally relevant to our species in many ways, and I think it’s likely that early positive experiences prior to 10 weeks or so in dogs mean that things they should fear as canids do not elicit a fear response. This unlearned response has heritable qualities, as Oddist Murphree demonstrated in pointers in the late 60s, and Scott & Fuller demonstrated across breeds in their seminal work. It’s also affected by development, both prenatally and postnatally. These fears would include pain responses and also constriction. The work of Arne Öhman and Susan Mineka as well as Robert Bolles are my go-to sources on things that are relevant to the species. Fear has adaptive value, as Joseph LeDoux says. Thus, waterboarding works because of our ancestral fear of drowning. Our body responds physiologically. Rats who have never been exposed to cats, for example, fear the odour of cats. These are a dog’s fear WHEN being restrained by a big predator like a human, for example. They’re afraid when stuff happens to them.

Then there are learned fears. These are the realm of Pavlov and Watson. Things that were formally neutral are paired up through associative learning because they predict an unconditioned stimulus will follow. Mark Bouton is my go-to scholar here. Rats can learn fear of lights and tones, but also of contexts, like the infamous Skinner Box or operant chamber itself. Dogs can learn to feel afraid OF vets and vet clinics. They’re afraid that stuff MIGHT happen to them.

Because humans are much less fussy about context, we forget about how relevant a context, location or environment can be in predicting unpleasant experiences. But a bit like me trying to struggle to truly empathise with dyslexic students, it’s easy to forget (and set up a blog with a serif font, for example, or forget to do the voice recording, because… Humans gonna human and we forget that our experience isn’t everyone else’s)

And then there are anxieties. Anxieties can also work off conditioned stimuli, but anxiety is also a mood state. It’s a cognitive, anticipatory state involving the expectation of unpleasant experiences - whether learned or innate.

In that experiment, I think there was huge potential that dogs learned to feel afraid in the first visit which affected what happened next.

Back to the paper… kind of

Everything we know about that second category - Pavlovian learned fear - says that it’s hefty learning ESPECIALLY when it comes first. If this is your primary experience and you felt afraid, your brain has got a really strong vested interest in protecting you from stuff.

For a gazillion reasons (well, at least six) our bodies may be primed to make us more prone to learn these fears. Genetics, gestational stress, maternal care, primary separation experience, early socialisation and single-event learning also contribute to how quickly we learn fears.

In other words, not all dogs are created the same. Our dogs are not JAX (r) mice, all genetically identical.

And these six reasons (and others) also contribute to how easily we find fears to get over. We also know, in no small part thanks to Mark Bouton, just how fragile that ‘getting over it’ learning is.

Learned fears come back easily and are not easily extinguished for many reasons: spontaneous recovery, renewal, reinstatement, resurgence and rapid reacquisition for some. Some of us are born with traits that also make it easier for learned fears to return, or harder.

Again, we’re not all identical JAX mice. Fear affects us differently. Some of us will hold on to it. Some of us will also struggle to create competing extinction learning that will fight against it. Nothing in the study ruled out initial susceptibility to fearfulness and it kind of assumed all the dogs were the same. Just as an example, one study in pre-print today (Krichbaum et al. 2023 in pre-print) on chewing in dogs split the dogs into ‘fearful’ vs ‘non-fearful’ using James Serpell’s CBARQ. Although it’s not a perfect method, at least it makes a nod to the fact that dogs are different and will experience fearful events in different ways. Damn you, confounding variables. Damn you!

Ok, properly back to the paper

First, what the researchers did was potentially create a fear conditioning experiment in a Skinner Box. They didn’t call it this, but that’s what it was.

‘Visit 1’ is the fear conditioning experiment. The dogs were there between 50-55 minutes. I once had to take Flika into the waiting room for 5 minutes and it was like trying to control a greased pig. Nothing had even happened to her. Heston panicked as soon as he couldn’t leave a strange setting, especially if I didn’t settle. That’s a long time for dogs, especially who underwent the wetting of fur, the application of ultrasound gel and the application of a monitor belt. Then the caregivers were instructed ‘to avoid interacting with the dog and to keep their dog on leash to prevent large movements.’

If you know me, you’ll know that I think humans are a form of social buffer. We reduce stress. How did these dogs interpret that removal of a social buffer? Frustrating and perhaps frightening, maybe. Plus, the restriction. Cut, once again, to me, wrestling an elderly Malinois.

In fact, go stand outside any vet treatment room in a shelter and see if waiting for ages adds to our diminishes arousal levels? Volunteers refused to come on vet days at the refuge… says it all!

What happens when you increase arousal levels?

You increase the likelihood of a fear response and sensitisation when they encounter an aversive stimulus or situation.

Then in Visit 1, the dogs were lifted by their caregivers. I had to pick Heston up once to walk him down a marble flight of stairs. He wet himself. I’m not sure if it was the picking up, the arousal & then the aversive experience or what, but it’s hard to know how expertly or inexpertly they handled their dogs, or, indeed, the size of caregiver to the size of the dog. I couldn’t even pick Tilly up easily and she was 9kg. Heston, at 35kg… was like Shaggy carrying Scooby.

Then the caregiver was asked to step back and not interact with the dog, whilst the dog was handled by the ‘vet’ (I say ‘vet’ because I’m not sure if Wess was acting as a vet or actually a vet, because the study says they ‘ took on the roles of the veterinarian’. Other than mild restraint '(holding the dog upright for three minutes on the table with one hand on the chest and one under the belly) that was visit 1. The dogs underwent a standard veterinary exam.

The chance of the dog having sensitised through arousal in the waiting room is pretty high, if you ask me. The chance of the dog then learning through Pavlovian associative learning the University clinic context, the vet and the table as part of the experiment is also not unlikely. Plus, it was the oncology department. We know dogs can smell cancer, and we don’t know what effect this will have had on sensitising them or in part of the contextual learning.

Those are all very valid reasons why this is potentially simple fear conditioning. The oncology lab is the Skinner Box, the wait, the table and the vet are the light predicting an aversive. The constraint and unavoidable aversive (the dogs were not able to escape because they were on a table and held in place by a human - albeit gently) are the shock through the floor. You can put treats in there all you like, but all they do is show disruption from normal patterns, just as the loaded food hopper in a Skinner Box might.

So for all intents and purposes, this is the dog’s first - potentially very aversive - experience. Fear conditioning at work.

Then there was an average 140 days before return where the control group and the test group diverged from their pathway. The test group had an average of 10 sessions that involved stepping on a mat as a ‘consent’ behaviour and then ‘desensitisation’ to handling. The guardians could then practise this at home.

Now I’m not being funny, but this is not cooperative care. It’s learning to tolerate aversive handling. That’s not cooperative care in my opinion. Cooperative care involves aversive handling, but this kind of procedure is not so much that. They were also trained to lie down and lie down with their head flat.

Visit Two

The second visit involved a return after an average of 140 days. There were a number of procedures, none of which were specifically trained for in the “cooperative care” process, and the mat was put on a table. In other words, it’s an inescapable situation unless you want to jump off the table.

Having possibly sensitised the dog to the initial experiences, there’s no evidence that specific habituation on an exposure gradient took place to the procedures that would be construed as aversive. In other words, the “desensitisation” may not have been specifically mapped to the sensitisation that had taken place. That may or may not be like trying to desensitise me to beeping reverse noises when I’m sensitive to thunder. Who knows?

There’s also no evidence that specific training took place related to the tests carried out in the second exercise.

And there’s no evidence that gradual exposure to the location took place.

They actually did less than I did between Heston’s “Visit 1” and Heston’s “Visit 2” because I at least I understood context a little bit.

What they did, then, may have been like many other researchers. They may have demonstrated that initial fear acquisition is incredibly robust and context-specific.

And they may have also demonstrated that extinction of fear learning is challenging when the learner re-encounters the unconditioned stimuli again.

This is the triple whammy of fear extinction failure: spontaneous recovery after a temporal delay; renewal when put back into the ‘A’ learning environment having learned extinction in a ‘B’ environment, and resurgence when the CS is re-paired with the US, as well as rapid reacquisition of fear because you’ve already sensitised the learner, and once sensitised, you’re easier to sensitise subsequently. Loads of reasons why overcoming fearful responses is really hard. And all of them were confounding variables in the experiment that were not accounted for. Nothing was done to try and address these known flaws in extinction learning

Whew.

For me, then, it was an experiment demonstrating what we already know. Fear learning is robust. Extinction learning is fragile.

And, to add it to it all, we don’t know if the dogs learned that escape brought an end to procedure during their learning trial. If they had, and they were then prevented from escaping, it’s likely escaping would return (reinstatement of instumentally learned behaviour when differential reinforcement fails).

But doesn’t this apply to both the control and the test group?

Kind of. You’d expect to see similar behaviours in both groups. Surely fear responses shouldn’t be more frequent, and physiological signs of stress more intense in the test group who had learned to step on a mat and learned to tolerate handling and learn to play dead?

It shouldn’t have been worse for the test group, surely?

Unless.

Firstly, it’s a small sample. It’s only 22 dogs in the test group and 18 dogs in the control. As someone who worked frequently with sample sizes of 200+, let me tell you that 10 individuals can throw your results out quite significantly. 10 individuals getting lower results in English and Maths than they were predicted in a secondary school size of 200 in the UK is the difference between success and an Ofsted inspection that will put you into special measures. Take it from someone whose job depended on finding those 10 students who could cause chaos to your results. It’s more like a primary school. 3 kids having a bad day on the KS2 exams is enough to generate significant fluctuations in your results. Ask me sometime about the difference in performance between testing in the place you taught the knowledge and testing in an exam hall, chewing gum of the same flavour you chewed in class, or smelling the same odour you smelled at the time you acquired your biology learning in GCSE science classes … small things can really change results. Plus, they didn’t control for initial fearfulness at all. That group of 22 dogs might have been accidentally more sensitive to fear learning than the control group.

Second, there’s a lot to unpick in this very, very interesting study. It sounds as if I’m pooh-poohing it. I am not. It is valiant work and I thoroughly enjoyed it. I do think it should have included at least some references to fear conditioning à la LeDoux, and extinction, à la Bouton, and maybe a little Bolles (1970). The references were a bit dogsy. Fear learning, extinction and safety learning are bigger than dogs. I’ve at least two more posts about this study in me and the actual numbers and findings are very interesting and potentially useful.

Anyway, statistical variations aside, there’s no evidence that the cooperative care protocol was generalised. They also spent a very long time in the waiting room which will have increased emotional and cognitive arousal no matter how they tried to mitigate for that. I know. I’ve stood outside vet rooms plenty of times with plenty of dogs. That second visit? Some of the dogs had to be carried in. Fool me once, and all that.

The other thing was that the main squirmy bit for the dogs was the rectal exam or femoral pulse reading. I reckon that’s fairly normal to cause panic. It is an unconditioned physiological response. Ask me sometime about the anal wink reflex. It’s a real thing. Sticking things up the rectum of most animals, or even tickling that orifice with water à la sea squirts, is enough to cause a response. That shouldn’t have affected the test group MORE though, which is interesting. Nevertheless, we can’t say ‘cooperative care doesn’t work’ off the back of this study, because it does work and we see it with our eyes every day.

If you didn’t prep the dog to have something go up its arse, then you didn’t really do cooperative care, if you ask me.

I taught Heston to present his back hind leg as a start button for the vet to do a blood draw with a large-gauge needle, and to hold steady. Yes, my dog whose anal glands gave way aged two. THAT’S my definition of cooperative care.

This is not a ‘I can do this’ competition, by the way. It’s just a ‘it can be done’ and ‘is done the world over’ statement, because it does work.

I also think that the cooperative care stuff may well have sensitised the dogs as well. In other words, sometimes when we think we’re desensitising with an exposure protocol, we’re actually sensitising them more. Remember, sensitivity to unconditioned stimuli will reset naturally and normally after a rest period. There are many sea squirts whose siphons have been sensitised who will attest to this. If you don’t actually give the dog a rest period after an aversive encounter with some unconditioned aversive stimulus, then you run the risk of sensitisation, not desensitisation. Maybe - just maybe - the care protocol between the two visits sensitised the dog to restraint. Who knows?

It’s certainly worth thinking about in my opinion.

Also, it’s no wonder they got freeze responses on Visit 1 and then avoidance responses on Visit 2, especially if the cooperative care protocol taught them that they could end the procedure. 17 dogs in the test group tolerated Visit 1, and 5 dogs terminated it (well, caregivers did) compared to 10 dogs tolerating Visit 2 and 12 dogs terminating it. Notably, they terminated it during procedures that were most intrusive (the rectal exam, mainly). The control group did not terminate the examination in the same way, suggesting I guess that having done nothing is better than having done something.

Or…. the control group had learned helplessness because they’d learned that nothing they did brought an end to the experience, whereas the test group learned to keep trying to terminate it. I’d be wanting to see some acknowledgement of Seligman in here, I think. We’ve had 50 years of learning about fear in dogs.

And a finally - although I’d expect to see this in both control and test dogs - they built up to the most aversive experience, meaning that the dogs had potentially less and less self-control to tolerate it.

What can we take from this?

I remain more and more convinced that safety cues can help us. Thinking back to my worst-case scenario, Barry the Rottweiler, and his blind, angry panic the very moment he turned the corner to the vet, how did we get him in?

First, we accepted that he needed sedation. Then we accepted that to sedate him, the vet would have to do some preliminary checks. We asked what they were. The vet said as a minimum, it would involve weighing and listening to his heart and lungs. We did have to take a high resolution photograph of his gums as well. Anyway, with those preliminaries, we were able to do cooperative care protocols specifically around stepping onto a platform for weighing. That included the non-slip mat of course. We also taught him to step into pressing his chest against a hand and then against a stethoscope, and to back off if he’d done.

Of course he was muzzled, and we used special pouches as a conditioned safety cue. We took sensible precautions to go when there were no other animals present and we changed vet surgery because, guess what, context is really important.

We also generalised his learning.

A lot of inexperienced cooperative care processes take place solely in the home. Sadly, this sets up an ABA renewal context. That’s to say, the vet’s office is A, where the fear happened. The home is B, where extinction learning takes place. Put the dog back in the vet (A) and it’s not unpredictable that fear will return (See Mark Bouton’s work on this… I’ll be sharing about some of its more important findings for dog trainers).

Barry had an ABCDEFG context, where he never went back to the initial vet surgery (nothing wrong with them - just trying to get a 50kg dog to overcome a phobia and strongly learned fear in 3 weeks without medication is beyond anybody’s capabilities I guess, unless they are Ken Ramirez or some such) and we generalised those skills like mad. Over those three weeks, he went into 10 safe places including hairdressers and warehouses and did cooperative care stuff with people. Well, facsimile cooperative care.

By the time he met that second vet, he was all ‘this is normal’ and also ‘this means we get burger later’. The vet listened to his heart and lungs. He weighed him. Then he prescribed him sedatives. Then we left and we went to eat burgers from McDo drive-thru.

The second vet actually didn’t think Barry needed sedation. Barry definitely needed sedation, but it goes to show that he really had no concept of just how dangerous and overwhelmed Barry could be once he’d been primed to be afraid.

This, by the way, is the same way I taught Heston, just when I was much crapper at it and hadn’t spent years perfecting skills.

What I did with Heston was swap surgeries. I took him to a vet I absolutely knew would treat him on the floor or allow me to cue him. Extinction behaviours are easier to retrieve if they are cued. We cued Barry too. We had five or six relatively hands-off short visits with food and practising his stuff. It really did not hurt that the new vet thought he was miraculous because he would open his mouth on cue and roll onto his back on cue. There was lots of love and no rectal examination or stabby stuff or being lifted onto a table.

The new surgery became a place that was not scary. When it got grabby and handly and restrictive, those were exceptions - even when they were the rule - to his original learning that the place was safe and even fun. It really did not hurt that time he saw a goat in the reception. He was very pleased to go to the vet from that day on.

What else?

I think we really, really need to take from this the fact that fear conditioning is powerful stuff. Put the fear in there and it becomes incredibly difficult to remove. In other words, stop causing fear on Visit 1 and then trying to push back against it.

Everything else that comes after is incredibly fragile learning that’s easily derailed.

If anything, we need to make sure Visits 1-5 (or maybe 6-8 if we want overlearning) are not aversive in any way. If we do that, our dogs are much less likely to develop learned fears of the vets in the first place.

Instead of 72 trials to try to desensitise and reduce fear (as one person did in the Wess trial) doing 5 trials preventing it first will be much more fruitful.

So many of us as caregivers are not aware that the vet will use constraint or restraint, treating dogs by lifting them onto the table and then giving them progressively more invasive tests while the dog is in a state of physiological arousal that is almost bound to sensitise them.

We can’t cause fear responses in that first visit and then say, ‘Oops!’ even if we do them in low-restraint ways. We can’t then expect the dog not to sensitise and struggle.

We also have to be mindful that cooperative care teaches dogs that they can opt out. If we can’t permit them to opt out, then initial fears will return. Reinstatement of avoidance behaviour is inevitable in those circumstances.

And finally, I think we all need a better understanding of (almost) involuntary fear responses to relevant threat, learned fears and more complex anxieties, phobias or panic. These are three distinctly different processes at a neural level and they demand different responses and treatment protocols.

Safety cues and retrieval cues for extinction behaviour will also be important.

Were I back in the shelter, I would have people in that vet room (or a vet-like room) every single day just eating cake and being friendly and I would make sure that every time volunteers came back from a walk with the dogs, they stopped off in there and gave the dog a treat for getting on the scale and so on. The difference that would make! I don’t have a single clue how you’d do that in real life vet clinics, but it’s sure easy in a shelter. I guess there would be insurance involved, but having the clinic open an extra two hours every day for walk throughs - literally walk in, eat food, do tricks, go out the back door - on a conveyor system, and an insistance that every new dog to the clinic should have done it at least 5 times if possible before treatment, and you’d have far fewer dogs needing medication, fewer anal glands giving way and fewer Barry Dogs trying to kill everyone on sight, like John Rambo having flashbacks to being tortured in Viet Nam. PS John Rambo’s escape from jail scene from First Blood is an almost perfect example of fear conditioning and renewal. It’s an almost perfect analogy for Barry at the first vets. More on THAT in future posts.

And if you need the tl;dr … we need to stop causing fear and then trying to push back against it. Prevent, not react.

I’ll be picking up on emotion research in future posts. I’ve got a few planned on the world beyond Panksepp. We’ll also be picking up on John Rambo for a couple of posts, even if you are not a fan of violent movies. I’ll be revisiting Lisa Feldman Barrett too - specifically her TED talk and book as opposed to her more reasoned academic literature (some of which I’m not at all in disagreement with, to be frank).

Feel free to let me know if there’s topics you’d like me to pick up! ps there will be voice recordings (podcasts, if you will!) for every future post. I’m old and the technology is hard sometimes when you used to record mixtapes off Radio 1 on an ancient cassette recorder and you remember Now That’s What I Call Music 2. I did try, I promise. Here’s to next week and me learning how to use a microphone in Substack!

References

Wess, L., Böhm, A., Schützinger, M., Riemer, S., Yee, J. R., Affenzeller, N., & Arhant, C. (2022). Effect of cooperative care training on physiological parameters and compliance in dogs undergoing a veterinary examination–A pilot study. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 250, 105615.

Bolles, R. C. (1970). Species-specific defense reactions and avoidance learning. Psychological review, 77(1), 32.

Bouton, M. E., & Ricker, S. T. (1994). Renewal of extinguished responding in a second context. Animal Learning & Behavior, 22, 317-324.

Bouton, M. E. (2004). Context and behavioral processes in extinction. Learning & memory, 11(5), 485-494.

Bouton, M. E., García-Gutiérrez, A., Zilski, J., & Moody, E. W. (2006). Extinction in multiple contexts does not necessarily make extinction less vulnerable to relapse. Behaviour research and therapy, 44(7), 983-994.

Brooks, D. C., & Bouton, M. E. (1993). A retrieval cue for extinction attenuates spontaneous recovery. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes, 19(1), 77.

Carlson, N. R., & Birkett, M. A. (2017). Physiology of behavior. Pearson Higher Ed.

Dykman, R. A., Murphree, O. D., & Reese, W. G. (1979). Familial anthropophobia in pointer dogs?. Archives of General Psychiatry, 36(9), 988-993.

Keltner, D., Oatley, K., & Jenkins, J. M. (2014). Understanding emotions. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

LeDoux, J. (2003). The emotional brain, fear, and the amygdala. Cellular and molecular neurobiology, 23, 727-738.

Öhman, A., & Mineka, S. (2001). Fears, phobias, and preparedness: toward an evolved module of fear and fear learning. Psychological review, 108(3), 483.

Panksepp, J. (2004). Affective neuroscience: The foundations of human and animal emotions. Oxford university press.

Scott, J. P., & Fuller, J. L. (1974). Dog behavior. Chicago, IL, USA:: University of Chicago Press.

Seligman, M. E. (1972). Learned helplessness. Annual review of medicine, 23(1), 407-412.

Wittgenstein, L. (1953). Philosophical investigations.